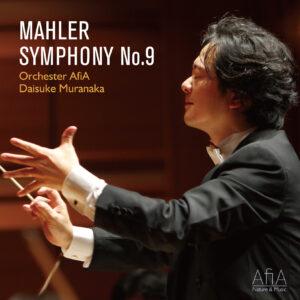

前回のルービンシュタインの考え方とは

スピリチュアルな意味でも

生演奏は人に少なからず影響をあたえることを

自身の演奏経験から

そしてまた自身のスピリチュアル体験からも

生演奏を拒否するグールドに伝えたかったようだけれど

さあ、グールド先生どう反論するか。

G.G.: Well, maybe so. Certainly, when you’re making a recording you are left alone. You’re not surrounded by five hundred, five thousand, fifty thousand people who are in a position to say at that moment, ” Aha, that’s what he thinks about that work, eh!” But that seems to me a great advantage. Because I think that the ideal way to go about making a performance or a work of art – and I don’t think that they should be different, really – is to assume that when you begin, you don’t quite know what it is about. You only come to know as you proceed. As you get two thirds of the way through the session, you are two thirds of the way along toward a conception. I very rarely know, when I come to the studio, exactly how I am going to do something. I mean, I ‘ll try it in fifteen different ways , and eight of them may work reasonably well, and there may be a possibility that two or three will sound really convincing. But I don’t know at the time of the session what result is finally saying , ” That doesn’t work; it isn’t going to go that way; I’ll have to change that completely. ” It makes the performer very like the composer, really, because it gives him editorial afterthought, it gives him that power – it’s a different kind of power than you were talking about, certainly, but it’s very real nontheless. Well, obviously, this is something that you cannot do in a concert, if only because you can’t stop, as I always wanted to , and say, ” Take two.”

A.R.: Well, yes , that is plausible. Recording is a different thing – it is a different affair. But do you do what I do? I make a few, you know, whole takes, and it’s very rare that I want to pick up anything. Sometimes, something happens with one wrong note, and you fix it like a false tooth – you just chip it off and replace it from the other take, you know , so it sounds right. But I like to play the whole thing once I ‘ve started because I cannot bear breaking it up.

G.G.: No, I can bear it because, first of all, I believe in editing. I agree that it’s helpful to make one full take per movement, but I see no particular reason why one couldn’t do something in one hundred and sixty-two different segments and never, in fact, do it straight through. I don’t work that way myself, but I see no reason why one couldn’t.

というわけで

ここで両者ガップリ四つに

持論展開です。

今書いていて思い出すのは

スヴィアトスラフ・リヒテルがウイーンで

よく夜の11時から演奏会を開いていた話です。

彼は録音嫌いで

録音をするとしても

絶対全曲を通すひとでした。

しかもライブ録音が殆どですし

思えばクライバーと共演したドヴォルザークのピアノ協奏曲と

ロストロポーヴィチと共演したベートーヴェンのチェロソナタ全曲録音ぐらいです。

スタジオ録音というのは。。。(もちろんもっとあるでしょうけれど。)

何故か。

やはり本番にはミューズの神が宿るといいますが

「目に見えないちから」を信じるということに

つきるのではないでしょうか。。。

極めて現実的なグールドの考えにすると

録音セッションのお蔭で

自分が曲自体の製作に

まるで作曲家のごとく

主導権を握れることで

演奏家の理想を実現することが可能になる。

ルービンシュタインは

演奏の本質は別のところに見ていて

何かが宿る瞬間や

空気感

そういったものを

演奏の真髄とする。

面白いですねえ。

まだまだ続きます。。。

To be continued…

最近のコメント